Abstract

Study design:

A questionnaire survey.

Objectives:

To evaluate the need for the introduction of quantitative diagnostic criteria for the traumatic central cord syndrome (TCCS).

Setting:

An online questionnaire survey with participants from all over the world.

Methods:

An invitation to participate in an eight-item online survey questionnaire was sent to surgeon members of AOSpine International.

Results:

Out of 3340 invited professionals, 157 surgeons (5%) from 41 countries completed the survey. Whereas most of the respondents (75%) described greater impairment of the upper extremities than of the lower extremities in their own TCCS definitions, symptoms such as sensory deficit (39%) and bladder dysfunctions (24%) were reported less frequently. Initially, any difference in motor strength between the upper and lower extremities was considered most frequently (23%) as a ‘disproportionate’ difference in power. However, after presenting literature review findings, the majority of surgeons (61%) considered a proposed difference of at least 10 points of power (based on the Medical Research Council scale) in favor of the lower extremities as an acceptable cutoff criterion for a diagnosis of TCCS. Most of the participants (40%) felt that applying a single criterion to the diagnosis of TCCS is insufficient for research purposes.

Conclusion:

Various definitions of TCCS were used by physicians involved in the spinal trauma care. The authors consider a difference of at least 10 motor score points between upper and lower extremity power a clear diagnostic criterion. For clinical research purposes, this diagnostic criterion can be considered as a face valid addendum to the commonly applied TCCS definition as introduced by Schneider et al.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1954, Schneider et al.1 were the first to describe ‘a syndrome that suggests central cervical spinal cord involvement’. This condition is now better known as traumatic central cord syndrome (TCCS). TCCS is characterized by (1) disproportionately more motor impairment of the upper than of the lower extremities; (2) bladder dysfunction, usually urinary retention and (3) varying degrees of sensory loss below the level of the lesion.1 Occurring mainly in elderly patients who have sustained a cervical hyperextension injury, it is reported that TCCS has been the most common spinal cord injury (SCI) syndrome, accounting for approximately 9% of all traumatic SCIs.2, 3, 4

Despite its frequency, uniform and globally accepted diagnostic criteria of TCCS are lacking. In the first of this three-article series, we concluded that various definitions had been applied in the original studies reporting on TCCS.5 Interestingly, none of the referenced studies provided specific neurological or functional eligibility criteria. A pragmatic analysis of pooled TCCS patients showed that, based on the Medical Research Council scale, the mean difference between strength of the upper and lower extremities was 10.5 motor score points in favor of the lower extremities.5

The introduction of quantitative diagnostic criteria allows clinicians to report on a more homogeneous, well-defined group of patients having TCCS. A minimum difference in strength between upper and lower extremities as proposed in part 1 may assist in distinguishing TCCS from other forms of incomplete tetraplegia. From one perspective, a diagnostic criterion based on a difference in motor strength alone may be seen as oversimplistic and that associated symptoms need consideration. Furthermore, the introduction of quantitative diagnostic TCCS criteria may be considered unnecessary due to a lack of impact on treatment decision-making.

To investigate the hypothetical tension between (1) the variety of applied diagnostic TCCS criteria among physicians, (2) the reduction and quantification of diagnostic parameters and (3) the clinical relevance of the TCCS diagnosis, we developed a questionnaire survey. The primary objective of this survey was to evaluate the need for the introduction of quantitative diagnostic criteria of TCCS among physicians involved in spinal trauma care and research. The secondary objective was to evaluate the face validity of the diagnostic criterion of a minimum difference of 10 motor score points between the upper and lower extremity power.5

Materials and methods

At the annual meeting of the European Multicenter Study of Human SCI network in Prague, Czech on 3 July 2009, the results of part 1 of this three-article series were presented and discussed.5 During this session several neurological reports of incomplete traumatic tetraplegic patients were also evaluated and discussed. It became clear that even among the scientifically active European Multicenter Study of Human SCI network, various interpretations of TCCS existed. This led us to the development of the questions of this study. An interactive pilot questionnaire survey was created and a group of 22 participants of the 48th International Spinal Cord Society annual scientific meeting in Florence, 21–24 October 2009, were found to participate. Based On the answers, comments and suggestions of these 22 participants, a definitive online survey version was created using Quizmaker ’09 (Articulate, New York, NY, USA). The survey items and questions are presented in Table 1a. Each question was presented on a separate webpage. The ‘browse backward’ option was disabled to prevent participants from correcting earlier answers, based on additional information provided in following questions.

To reach a large number of specialists in spinal trauma care, we contacted the secretary of the AOSpine Research Commission. The AOSpine community is an established organization with a considerable number of orthopedic and neurosurgeons actively involved in the diagnosis, treatment and study of SCI. On 10 December 2009, an invitation to participate in the online questionnaire survey was sent to AOSpine community members. The website of the online survey was closed at 31 December 2009. Data concerning physicians’ specialties were extracted from the membership databases. Before the data analysis, answers to open-ended questions were recoded independently by two reviewers (JJvM and MHP). The data were entered into spreadsheets and in Excel (Office Excel 2003; Microsoft) for descriptive analysis. Post hoc χ2-analyses were applied to evaluate the relation between the participants’ duration of experience in the clinical field of SCI (two subgroups: <5 years versus ⩾5 years) and the categorical survey answers.

Results

Characteristics of responders

An invitation to participate in the questionnaire survey was sent to 3340 professionals. Complete responses were received from 157 professionals (5% response rate), including 62 (39%) orthopedic surgeons, 47 (30%) spine surgeons, 43 (27%) neurosurgeons and 5 (3%) residents orthopedic surgery. The respondents represented 41 countries from all six major regions of the world (Figure 1). The mean duration of participants’ experience in the clinical field of SCI was 9.1 years (range 1–29 years) with 95 surgeons (61%) having a minimum of 5 years of experience. In survey questions with categorical answers, no statistically significant differences were found between the subgroups of participants with less or more than 5 years of experience.

Applied TCCS definitions (question 1)

Various answers were given to the question ‘What is your definition of traumatic central cord syndrome?’ (Table 2). The majority of respondents included neurological (91%) and/or functional (4%) impairment in their definition. Most of the physicians (75%) described the typical disproportionate upper limb motor loss. Less than half of the respondents included sensory deficit (39%) or bladder dysfunctions (24%) as symptoms of TCCS. Only 36 physicians (23%) described all three classical features of the TCCS as defined by Schneider et al.1

Other characteristics than neurological and functional signs and symptoms associated with TCCS were documented as well. Approximately 15% of respondents described the elderly patient with a preexistent stenotic, spondylotic spinal canal sustaining a hyperextension injury as being at highest risk for TCCS. A minority of physicians applied neuroanatomical explanatory descriptives (20%; for example, ‘affected corticospinal tracts’) and the anticipated findings of spinal cord imaging (6%; for example, ‘intramedullary high-signal intensity on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)’) as essential items in the definition of TCCS (Table 2).

Need for diagnostic TCCS criteria (questions 2, 3 and 4)

With regard to clinical practice, communication and treatment decision-making, the majority of surgeons (71%) considered their own TCCS definition satisfactory (Table 1b). Of the remaining surgeons, 32 (20%) were not satisfied with their current definition. Referring to the ‘Schneider definition’, 22 physicians (14%) stated that the TCCS definition is an ambiguous one, which is lacking in precision. Another stated reason for the lack of physicians' support for the current TCCS definition was a perceived lack of clinical relevance and use (8%).

Even with physicians’ general acceptance of the clinical applicability of the TCCS definition (71%), the majority of respondents (95%) acknowledged the need for diagnostic criteria for research purposes. Physicians of this latter group were asked to provide the necessary diagnostic items for inclusion in such criteria. Although various diagnostic items similar to answers provided in question 1 were proposed, none of the respondents suggested a specific cutoff criterion.

Disproportionate difference of motor loss (question 5)

As presented in Table 3, physicians’ interpretation of the disproportionate difference of motor loss varied considerably. The interpretations of a disproportionate difference in strength as reported by the respondents can be categorized as (1) absolute or (2) proportionate difference between the upper extremity motor score and lower extremity motor score and (3) a threshold difference of the manual muscle test grades of the affected key muscles between the upper (that is, 0–2) and lower extremities (that is, 3–5).6 Even within these approaches many interpretations existed (Table 3). Remarkably, any difference between the strength of the upper and lower extremities in favor of the lower extremities (23%) was frequently considered a disproportionate difference. In all, 55 physicians (35%) did not report their interpretation of a disproportionate difference and another 11 physicians (7%) continued reporting a ‘disproportionate difference’ without any further specification.

Diagnostic TCCS criterion and prognosis (questions 6, 7 and 8)

Respondents were asked their opinion of the diagnostic criterion of TCCS as proposed in the first of this three-article series (Intermezzo 2, Table 1a).5 The majority of physicians (61%) considered a minimal difference of 10 motor score points between the upper and lower extremities in favor of the lower extremities as an acceptable cutoff criterion for research purposes. Of the remaining surgeons, 23 (15%) had no opinion and 28 (24%) did not agree with the proposed diagnostic criterion and/or cutoff level. In addition, 13 respondents (8%) of this latter group suggested applying a minimum difference of <10 motor score points between upper and lower limb power. In contrast, four respondents (3%) suggested a minimum difference of >10 points as a diagnostic criterion.

Physicians were also asked whether they agreed or disagreed that the proposed ‘10 motor score points difference’ approach is too simplistic to accurately identify TCCS patients for clinical trials. Although 57 respondents (36%) regarded this as a valid approach, most respondents (40%) regarded this approach oversimplistic (Table 1b). The latter group suggested that the following areas also need to be covered by the following diagnostic criteria: findings of spinal cord imaging (11%), sensory deficit (4%), bladder dysfunction 4%, level of injury (3%), sacral sparing (3%), neurophysiological parameters (2%) and others. However, as given in question 4, none of the respondents suggested a specific cutoff criterion in combination with their proposed additional diagnostic item.

Finally, participants were asked their opinion of the prognosis of recovery in TCCS patients. Most of the participating surgeons (76%) held the opinion that TCCS had a favorable prognosis for neurological and/or functional recovery compared with non-TCCS incomplete tetraplegic patients (Table 1b).

Discussion

This survey study shows that a wide range of TCCS definitions are in use among physicians involved in spinal trauma care. Although the majority of the respondents apply their own TCCS definitions in clinical applications, most physicians agree on the need for the more specific diagnostic criteria in the setting of research. The majority of physicians considered a difference in motor score of at least 10 points as an acceptable cutoff criterion, however, the majority of the respondents also felt that applying a single criterion to the diagnosis of TCCS would be insufficiently accurate for clinical research purposes.

In the recent past, the historical report of Schneider et al.1 has been challenged. Not only have the original descriptions of pathogenesis and neuroanatomical basis of TCCS been criticized,7, 8, 9, 10, 11 but optimal treatment of the condition has also been reappraised.3, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 This survey study challenges the ambiguity of the TCCS definition as introduced by Schneider et al. Whereas several physicians assign a diagnosis of TCCS in SCI patients with only 1 motor score point lower in the upper extremities than in the lower extremities, other physicians consider patients with a minimum difference of 15 points as TCCS patients. In part 1 we showed that clinical researchers also apply various approaches in assigning a diagnosis of TCCS.5 Obviously, a lack of uniform diagnostic criteria in clinical studies may limit the translational potential of results.

In the most recent revision of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (2002), the CCS is defined as ‘a lesion, occurring almost exclusively in the cervical region, that produces sacral sensory sparing and greater weakness in the upper limbs than in the lower limbs.’ Interestingly, items from the original ‘Schneider definition’ including bladder dysfunction and varying degrees of sensory loss have been omitted from this consensus-based definition. Concurrent findings of this study showed that the presence of sensory deficit and bladder dysfunction were reported as TCCS descriptives by only 39 and 24%, respectively, of this survey's respondents. From a practical point of view, distinguishing TCCS patients from other incomplete tetraplegic patients on the basis of specific cutoff criteria for bladder dysfunction and varying degrees of sensory loss would be a difficult, if not impossible, task. However, as the Schneider definition is the most commonly reported definition of TCCS,5 we adhered to this definition by introducing a quantitative addendum to the description ‘disproportionately more motor impairment of the upper than of the lower extremities’.1 Approximately one out of ten respondents suggested the introduction of additional diagnostic criteria based on spinal cord imaging. Although clinically relevant correlations between acute-phase magnetic resonance imaging findings and neurological outcomes have been reported in SCI patients, no studies reporting significant correlation between magnetic resonance imaging findings and initial neurological examination results have been published to date.17, 18, 19, 20 Nonetheless, as diagnostic imaging technology continues to evolve, future modification of SCI syndrome definitions may occur.

The clinical relevance of TCCS was questioned in 8% of the responses provided by surgeons. Indeed, from a neurological point of view, TCCS can be considered as tetraplegia with sparing of the sacral segments. Interestingly, 76% of the responding physicians had the opinion that TCCS patients have a better outlook than non-TCCS incomplete tetraplegic patients. Although strong evidence supporting this common opinion is currently missing, this finding clearly illustrates that—in terms of natural history—TCCS is considered a clinically relevant entity by the majority of surgeons.21 This finding is supported by a panel of SCI experts from the International Campaign for Cures of Spinal Cord Injury Paralysis, who published four reference works appraising methodological issues for the conduct of clinical trials in SCI.22, 23, 24 Referring to higher spontaneous rates of overall sensory and motor recovery in TCCS, the expert panel considered TCCS patients ‘not being the best subjects to be included with other types of traumatic SCI during a phase 1 or phase 2 trial, as they could increase the variability of the outcome data’.24 To examine the hypothesis that TCCS patients truly have a higher rate of neurological recovery, the use of a clear diagnostic criterion may be of great benefit.

To illustrate, in future clinical comparative studies incomplete tetraplegic patients may be stratified into three groups: (1) those with equal or less power in the lower limbs, (2) those with 1–9 points more power in the lower limbs and (3) those with 10 points or more power in the lower limbs compared with the upper limbs. If multiple studies would show that patients in group 3 indeed do have higher spontaneous rates of overall recovery than those in group 1, then the assumptions of the majority of the responding surgeons and the International Campaign for Cures of Spinal Cord Injury Paralysis expert panel would be confirmed. This in turn will justify a subsequent evaluation of the possibilities to adjust the currently proposed diagnostic criterion into a less conservative one (that is, <10 points difference).25 Yet, if the hypothesis would be rejected, then the clinical relevance of the TCCS in terms of natural history and acute phase treatment decision-making should, again, be reappraised critically.3 These two scenarios clearly illustrate the importance of clear and unambiguous definitions for patient stratification in SCI research. A face valid, quantitative diagnostic criterion as presented in this three-article series may facilitate this patient selection.26

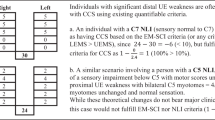

Several limitations to the proposed criterion require consideration. A substantial number of surgeons initially considered any difference of motor strength between the upper and lower extremities as a disproportionate difference. Furthermore, some respondents regarded the proposed minimum difference of 10 motor score points too high. From a clinical point of view, a difference of 1 motor score point between the upper and lower extremities does not reflect a ‘clinically significant’ difference in strength between TCCS and other incomplete tetraplegic patients. The same can be said for the ‘proportional difference’ approach when applied in patients with a more severe deficit in the lower limbs (for example, the upper extremity motor score/lower extremity motor score: 40/50 (=20%) compared with 16/20 (=20%)). Nonetheless, as illustrated in Box 1, clinically evident TCCS patients—in particular those with lower cervical level of injuries—may not be categorized as TCCS patients by applying our proposed criterion. Although we did not find an identical case as presented in Box 1 in the European Multicenter Study of Human SCI database (no. of traumatic SCI patients >1000), we acknowledge that the proposed criterion is a quite conservative one, lacking optimal (clinical) sensitivity. As outlined earlier, the use of our proposed diagnostic criterion in future studies would inevitably result in a selection of more outspoken TCCS patients compared with those patients described in studies included for review in part 1.5 Moreover, by applying our proposed criterion the proportion of quantitatively diagnosed TCCS patients would be less in future studies. This may increase the risk of not detecting significant effects (type II error) in following comparative studies.23 Hence, future clinical studies comparing the recovery of incomplete tetraplegic and TCCS patients should ideally be performed in large multicenter networks.

Another aspect that requires consideration is the timing of examination. It has been documented that the motor power returns earlier to the lower than to the upper limbs in TCCS patients.3 This means that the difference of motor strength between the upper and lower limbs increases during the initial phase of recovery. To illustrate, whereas the difference in power between the upper and lower limbs may be 8 points 24 h after injury (Box 1), this difference may be increased to 10 or even more points 1 week after the injury. To improve the applicability of the proposed cutoff criterion for (acute) TCCS, we therefore suggest to extend the scientific applicability of the diagnostic criterion to the first 2 weeks after injury.27 We acknowledge that this standardization of timing is quite arbitrary. However, this indicative time frame may result in an increased sensitivity of the diagnostic criterion and also an improved homogeneity of future TCCS study populations. To gain more insight in the initial recovery patterns of incomplete tetraplegics and TCCS patients, further descriptive studies are warranted.

In this survey a substantial number of surgeons described the elderly patient with a preexistent stenotic, spondylotic spinal canal sustaining a hyperextension injury as being at highest risk for TCCS.1, 28 Several reports proposed the benefit of surgical treatment in elderly TCCS patients with a preexistent degenerative cervical spine for the prevention of late neurological deterioration or progressive chronic myelopathy.2, 29, 30 This suggestion may shed a new light on the earlier mentioned clinical relevance of TCCS in the elderly patients. Nevertheless, no study evaluating the differences in preexistent degenerative changes of the cervical spine and late onset neurological deterioration between elderly patients with incomplete tetraplegia and TCCS has been published to date. Also from this point of view well-conducted clinical studies comparing the recovery of incomplete tetraplegic and TCCS patients are warranted.

The main strength of this survey study is the large number of participating spine specialists from all over the world. Although the response rate was low, the sample size is relatively large. A possible explanation for the low response rate may be that not all AOSpine members are involved in spinal trauma care. Another limitation of the power of this survey's finding is the absence of rehabilitation specialists. Although the International Spinal Cord Society secretary was contacted at an early stage, the digital infrastructure of this organization did not allow us to reach a large number of rehabilitation specialists. Nonetheless, a number of rehabilitation specialists were involved in development of the questionnaire and study design. Following previous questionnaire surveys in the field of SCI and spinal surgery, this survey study reinforces the notion that, by gathering experts’ opinions, a clear insight can be obtained into controversial issues.31, 32, 33 International scientific organizations like the AOSpine and International Spinal Cord Society can have an important facilitating role in such important scientifically and clinically orientated collaborative research initiatives.

Conclusion

This survey study found that a wide range of definitions of TCCS exist among physicians involved in spinal trauma care. Although the majority of respondents expressed their desire to apply their own TCCS definitions in a clinical setting, most physicians agreed on the need for more specific diagnostic criteria for scientific purposes. Based on the results of the first two studies of this three-article series, the authors consider a difference of at least 10 motor score points between the upper and lower extremities a clear diagnostic criterion. Applying this additional diagnostic criterion in future SCI studies may result in more clearly defined patient samples and improved translational potential of results. Prior to the endorsement of the proposed diagnostic criterion for TCCS, future clinical validation studies are necessary.

References

Schneider RC, Cherry G, Pantek H . The syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury; with special reference to the mechanisms involved in hyperextension injuries of cervical spine. J Neurosurg 1954; 11: 546–577.

Bosch A, Stauffer ES, Nickel VL . Incomplete traumatic quadriplegia: a ten-year review. JAMA 1971; 216: 473–478.

Merriam WF, Taylor TK, Ruff SJ, McPhail MJ . A reappraisal of acute traumatic central cord syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1986; 68: 708–713.

McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K . Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 215–224.

Pouw MH, van Middendorp JJ, van Kampen A, Hirschfeld S, Veth RP, Curt A et al. Diagnostic criteria of traumatic central cord syndrome. Part 1: A systematic review of clinical descriptors and scores. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 652–656.

American Spinal Injury Association. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury, Revised 2002. American Spinal Injury Association: Chicago, IL, 2002.

Collignon F, Martin D, Lenelle J, Stevenaert A . Acute traumatic central cord syndrome: magnetic resonance imaging and clinical observations. J Neurosurg 2002; 96 (1 Suppl): 29–33.

Jimenez O, Marcillo A, Levi AD . A histopathological analysis of the human cervical spinal cord in patients with acute traumatic central cord syndrome. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 532–537.

Levi AD, Tator CH, Bunge RP . Clinical syndromes associated with disproportionate weakness of the upper versus the lower extremities after cervical spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery 1996; 38: 179–183;discussion 83–85.

Martin D, Schoenen J, Lenelle J, Reznik M, Moonen G . MRI–pathological correlations in acute traumatic central cord syndrome: case report. Neuroradiology 1992; 34: 262–266.

Quencer RM, Bunge RP, Egnor M, Green BA, Puckett W, Naidich TP et al. Acute traumatic central cord syndrome: MRI-pathological correlations. Neuroradiology 1992; 34: 85–94.

Bose B, Northrup BE, Osterholm JL, Cotler JM, DiTunno JF . Reanalysis of central cervical cord injury management. Neurosurgery 1984; 15: 367–372.

Brodkey JS, Miller Jr CF, Harmody RM . The syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury revisited. Surg Neurol 1980; 14: 251–257.

Chen L, Yang H, Yang T, Xu Y, Bao Z, Tang T . Effectiveness of surgical treatment for traumatic central cord syndrome. J Neurosurg Spine 2009; 10: 3–8.

Chen TY, Dickman CA, Eleraky M, Sonntag VK . The role of decompression for acute incomplete cervical spinal cord injury in cervical spondylosis. Spine 1998; 23: 2398–2403.

Newey ML, Sen PK, Fraser RD . The long-term outcome after central cord syndrome: a study of the natural history. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000; 82: 851–855.

Mahmood NS, Kadavigere R, Avinash KR, Rao VR . Magnetic resonance imaging in acute cervical spinal cord injury: a correlative study on spinal cord changes and 1 month motor recovery. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 791–797.

Miyanji F, Furlan JC, Aarabi B, Arnold PM, Fehlings MG . Acute cervical traumatic spinal cord injury: MR imaging findings correlated with neurologic outcome—prospective study with 100 consecutive patients. Radiology 2007; 243: 820–827.

Ramon S, Dominguez R, Ramirez L, Paraira M, Olona M, Castello T et al. Clinical and magnetic resonance imaging correlation in acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 664–673.

Shepard MJ, Bracken MB . Magnetic resonance imaging and neurological recovery in acute spinal cord injury: observations from the national acute spinal cord injury study 3. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 833–837.

Harrop JS, Sharan A, Ratliff J . Central cord injury: pathophysiology, management, and outcomes. Spine J 2006; 6 (6 Suppl): 198S–206S.

Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 190–205.

Lammertse D, Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Rask C et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial design. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 232–242.

Steeves JD, Lammertse D, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Tuszynski MH, Ditunno JF et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial outcome measures. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 206–221.

Hayes KC, Hsieh JT, Wolfe DL, Potter PJ, Delaney GA . Classifying incomplete spinal cord injury syndromes: algorithms based on the international standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 644–652.

Tuszynski MH, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW, Lammertse D, Kalichman M, Rask C et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP Panel: clinical trial inclusion/exclusion criteria and ethics. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 222–231.

Kirshblum SC, O’Connor KC . Predicting neurologic recovery in traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79: 1456–1466.

Epstein N, Epstein JA, Benjamin V, Ransohoff J . Traumatic myelopathy in patients with cervical spinal stenosis without fracture or dislocation: methods of diagnosis, management, and prognosis. Spine 1980; 5: 489–496.

Song J, Mizuno J, Inoue T, Nakagawa H . Clinical evaluation of traumatic central cord syndrome: emphasis on clinical significance of prevertebral hyperintensity, cord compression, and intramedullary high-signal intensity on magnetic resonance imaging. Surg Neurol 2006; 65: 117–123.

Stevens EAMD, Powers AKMD, Branch CLJMD . The role of surgery in traumatic central cord syndrome. Neurosurg Q 2009; 19: 222–227.

Kwon BK, Hillyer J, Tetzlaff W . Translational research in spinal cord injury: a survey of opinion from the SCI community. J Neurotrauma 2010; 27: 21–33.

Busse JW, Jacobs C, Ngo T, Rodine R, Torrance D, Jim J et al. Attitudes toward chiropractic: a survey of North American orthopedic surgeons. Spine 2009; 34: 2818–2825.

Molloy S, Price M, Casey AT . Questionnaire survey of the views of the delegates at the European Cervical Spine Research Society meeting on the administration of methylprednisolone for acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Spine 2001; 26: E562–E564.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participating members of the European Multicenter Study of Human Spinal Cord Injury (EM-SCI) and the 48th ISCoS annual scientific meeting participants for their cooperation in the preparation of this study. We also thank Dr John F Ditunno Jr for his thorough and insightful comments during earlier phases of this study. We are grateful to the AOSpine International employees, with special thanks to Michael Fawcett, Vera Capaul and Mary Anne Smith, for their enthusiasm and willingness to facilitate this survey study. We acknowledge the participating AOSpine members for their time, answers and valuable comments on the survey. This study was supported by ‘Acute Zorgregio Oost’ and the ‘Internationale Stiftung für Forschung in Paraplegie (IFP)’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Middendorp, J., Pouw, M., Hayes, K. et al. Diagnostic criteria of traumatic central cord syndrome. Part 2: A Questionnaire Survey among Spine Specialists. Spinal Cord 48, 657–663 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.72

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.72

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) and minimal detectable change (MDC) of Spinal Cord Ability Ruler (SCAR)

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Central cord syndrome definitions, variations and limitations

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Does surgery improve neurological outcomes in older individuals with cervical spinal cord injury without bone injury? A multicenter study

Spinal Cord (2022)

-

Is it time to redefine or rename the term “Central Cord Syndrome”?

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Comparison of outcomes between people with and without central cord syndrome

Spinal Cord (2020)